Universal Design Principles and Goals

Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State University – Universal Design Definition, Principles, and Guidelines

Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access (IDeA), University at Buffalo, NY – Universal Design Definition and Goals

Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State University – Universal Design Definition, Principles, and Guidelines

Definition: Architect Ron Mace defined Universal Design as “The design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.”

The authors, a working group of architects, product designers, engineers and environmental design researchers, collaborated to establish the following Principles of Universal Design to guide a wide range of design disciplines including environments, products, and communications. These seven principles may be applied to evaluate existing designs, guide the design process and educate both designers and consumers about the characteristics of more usable products and environments.

The Principles of Universal Design are presented here, in the following format: name of the principle, intended to be a concise and easily remembered statement of the key concept embodied in the principle; definition of the principle, a brief description of the principle’s primary directive for design; and guidelines, a list of the key elements that should be present in a design which adheres to the principle. (Note: all guidelines may not be relevant to all designs.)

PRINCIPLE ONE: Equitable Use

The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

Guidelines:

1a. Provide the same means of use for all users: identical whenever possible; equivalent when not.

1b. Avoid segregating or stigmatizing any users.

1c. Provisions for privacy, security, and safety should be equally available to all users.

1d. Make the design appealing to all users.

PRINCIPLE TWO: Flexibility in Use

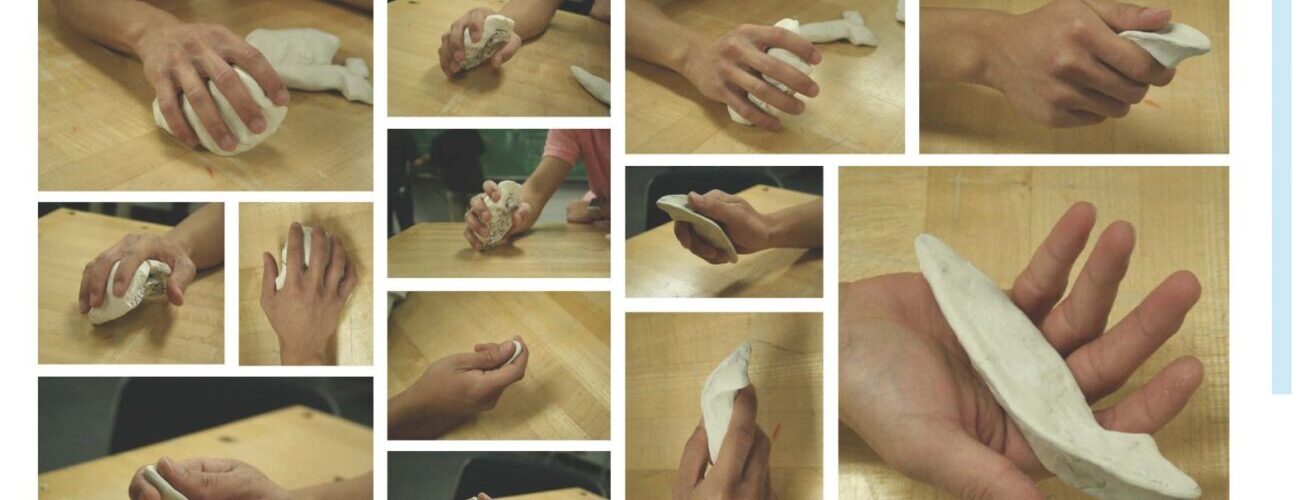

The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

Guidelines:

2a. Provide choice in methods of use.

2b. Accommodate right- or left-handed access and use.

2c. Facilitate the user’s accuracy and precision.

2d. Provide adaptability to the user’s pace.

PRINCIPLE THREE: Simple and Intuitive Use

Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level.

Guidelines:

3a. Eliminate unnecessary complexity.

3b. Be consistent with user expectations and intuition.

3c. Accommodate a wide range of literacy and language skills.

3d. Arrange information consistent with its importance.

3e. Provide effective prompting and feedback during and after task completion.

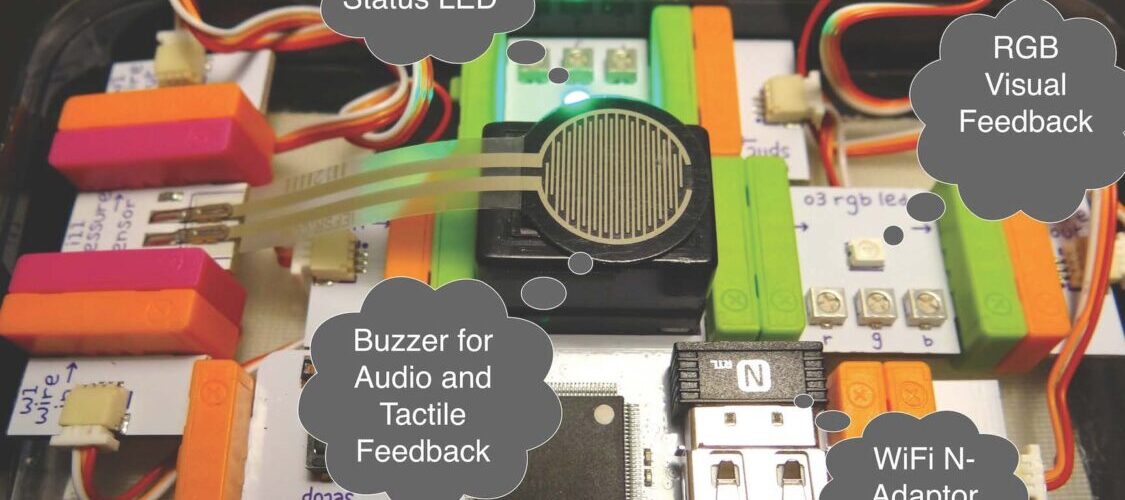

PRINCIPLE FOUR: Perceptible Information

The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities.

Guidelines:

4a. Use different modes (pictorial, verbal, tactile) for redundant presentation of essential information.

4b. Provide adequate contrast between essential information and its surroundings.

4c. Maximize “legibility” of essential information.

4d. Differentiate elements in ways that can be described (i.e., make it easy to give instructions or directions).

4e. Provide compatibility with a variety of techniques or devices used by people with sensory limitations.

PRINCIPLE FIVE: Tolerance for Error

The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

Guidelines:

5a. Arrange elements to minimize hazards and errors: most used elements, most accessible; hazardous elements eliminated, isolated, or shielded.

5b. Provide warnings of hazards and errors.

5c. Provide fail safe features.

5d. Discourage unconscious action in tasks that require vigilance.

PRINCIPLE SIX: Low Physical Effort

The design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with a minimum of fatigue.

Guidelines:

6a. Allow user to maintain a neutral body position.

6b. Use reasonable operating forces.

6c. Minimize repetitive actions.

6d. Minimize sustained physical effort.

PRINCIPLE SEVEN: Size and Space for Approach and Use

Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of user’s body size, posture, or mobility.

Guidelines:

7a. Provide a clear line of sight to important elements for any seated or standing user.

7b. Make reach to all components comfortable for any seated or standing user.

7c. Accommodate variations in hand and grip size.

7d. Provide adequate space for the use of assistive devices or personal assistance.

Please note that the Principles of Universal Design address only universally usable design, while the practice of design involves more than consideration for usability. Designers must also incorporate other considerations such as economic, engineering, cultural, gender, and environmental concerns in their design processes. These Principles offer designers guidance to better integrate features that meet the needs of as many users as possible.

Copyright 1997 NC State University, The Center for Universal Design

Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access (IDeA), University at Buffalo, NY – Universal Design Definition and Goals

Definition: Universal design “a design process that enables and empowers a diverse population by improving human performance, health and wellness, and social participation” (Steinfeld and Maisel, 2012).

Goals of Universal Design

The IDeA Center developed a new conceptual framework for universal design that expands the original usability focus to social participation and health and acknowledges the role of context in developing realistic applications. Complementing the Principles of UD (NCSU, 1997), the Goals of Universal Design© define the outcomes of UD practice in ways that can be measured and applied to all design domains within the constraints of existing resources. In addition, they encompass functional, social, and emotional dimensions. Moreover, each goal is supported by an interdisciplinary knowledge base (e.g., anthropometrics, biomechanics, perception, cognition, safety, health promotion, social interaction). Thus, the Goals can be used effectively as a framework for both knowledge discovery and knowledge translation for practice. Moreover, the Goals can help to tie policy embodied in disability rights laws to UD and provide a basis for improving regulatory activities by the adoption of an outcomes-based approach.

Visit udeworld.com/goalsofud.html for visual and descriptive real-world examples of each Goal.

Body Fit

Accommodating a wide a range of body sizes and abilities

Comfort

Keeping demands within desirable limits of body function and perceptio

Awareness

Ensuring that critical information for use is easily perceived

Understanding

Making methods of operation and use intuitive, clear and unambiguous

Wellness

Contributing to health promotion, avoidance of disease and protection from hazards

Social Integration

Treating all groups with dignity and respect

Personalization

Incorporating opportunities for choice and the expression of individual preferences

Cultural Appropriateness

Respecting and reinforcing cultural values, and the social and environmental contexts of any design project

If you would like to reference the Goals of Universal Design, please credit “Steinfeld and Maisel, 2012”

The Cinch hamper simplifies the laundry process for all individuals, especially those with limited mobility (e.g., aging, disability, health challenges, injuries). Storage, transportation, folding, and hanging laundry are physically strenuous tasks due to required lifting, bending, and range-of-motion. The Cinch hamper employs mechanical advantage to do the lifting and transport of clothing for the user, while providing a simplified system for clothes hanging. Clothing remains at waist height for unloading to/from washer; wheeled transport with storage eliminates need for laundry baskets.

The Cinch hamper simplifies the laundry process for all individuals, especially those with limited mobility (e.g., aging, disability, health challenges, injuries). Storage, transportation, folding, and hanging laundry are physically strenuous tasks due to required lifting, bending, and range-of-motion. The Cinch hamper employs mechanical advantage to do the lifting and transport of clothing for the user, while providing a simplified system for clothes hanging. Clothing remains at waist height for unloading to/from washer; wheeled transport with storage eliminates need for laundry baskets.

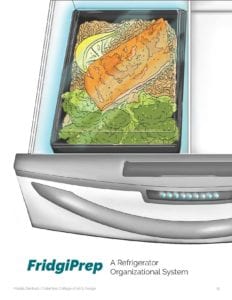

People who are experiencing memory loss can develop disordered eating habits, and often do not get the proper nutrition they need. They may forget how to make balanced meals or cook altogether. Taking inspiration from pill organizers and the booming grocery delivery and meal kit markets, FridgiPrep addresses this issue with drawers that are divided into compartments corresponding with meals to be eaten per day. It beeps when it is time to eat, and LED lights glow to indicate which section contains the meal to be eaten. FridgiPrep was designed to be installed into existing refrigerator drawers.

People who are experiencing memory loss can develop disordered eating habits, and often do not get the proper nutrition they need. They may forget how to make balanced meals or cook altogether. Taking inspiration from pill organizers and the booming grocery delivery and meal kit markets, FridgiPrep addresses this issue with drawers that are divided into compartments corresponding with meals to be eaten per day. It beeps when it is time to eat, and LED lights glow to indicate which section contains the meal to be eaten. FridgiPrep was designed to be installed into existing refrigerator drawers.

The WCY Wheelchair aims to address the challenge of transferring an individual from a wheelchair to a seat on the plane. The WCY includes a sliding seat that acts as a bridge or transfer board. Passengers do not have to leave the support seat during the transfer process, thus eliminating the need to be lifted up. This solution saves airport staff persons’ energy, and offers a better experience for the passenger. The wheelchair can be folded and carried as a suitcase while traveling. Its narrow width and foldable design bring benefits to a variety of environments beyond the airport.

The WCY Wheelchair aims to address the challenge of transferring an individual from a wheelchair to a seat on the plane. The WCY includes a sliding seat that acts as a bridge or transfer board. Passengers do not have to leave the support seat during the transfer process, thus eliminating the need to be lifted up. This solution saves airport staff persons’ energy, and offers a better experience for the passenger. The wheelchair can be folded and carried as a suitcase while traveling. Its narrow width and foldable design bring benefits to a variety of environments beyond the airport. Mary Lou Dauray, CID

Mary Lou Dauray, CID