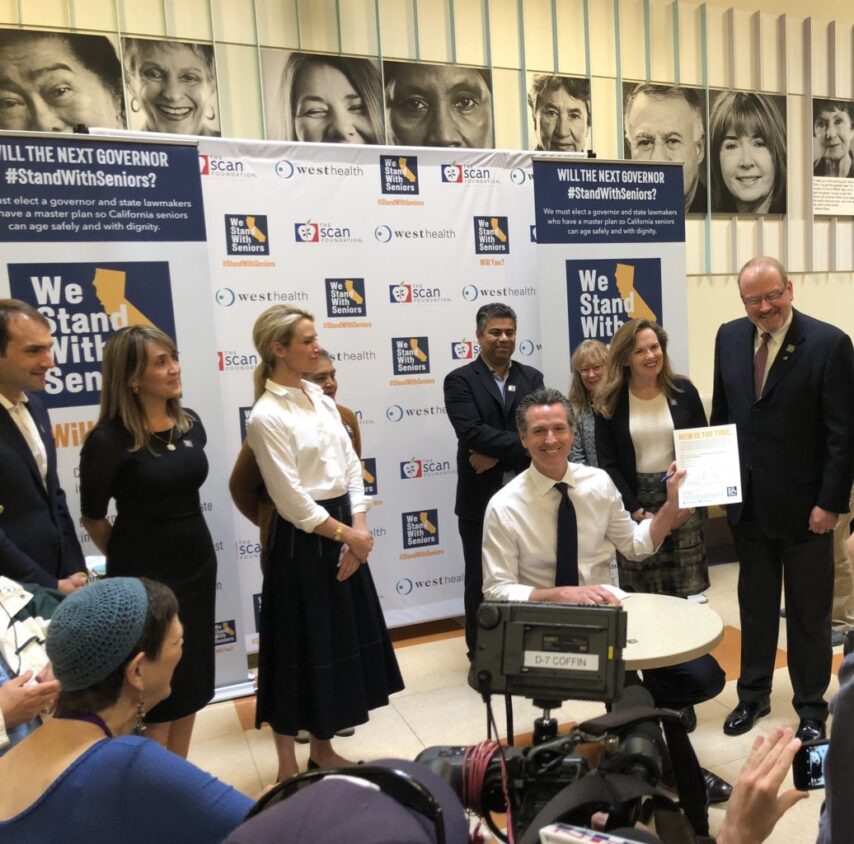

Christian Pike, Professor of Gerontology at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, discusses his research on sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease and how they can help inform how we might one day prevent and treat it.

Quotes from this episode

“… Maybe there are situations where the disease, although it’s the same disease, it works a little bit different in men than it does women. And maybe we should consider that in terms of the risk factors for developing it and even how we approach it therapeutically.”

“If you look at clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease drugs, almost all of them are failed.”

“You can’t control your genetics. At least you can’t yet. But you can control your environment and your lifestyle what we call modifiable risk factors. And so what everybody can do is deal with those now. while we’re, while we’re waiting to get the treatments.”

“There are so many differences between men and women in Alzheimer’s disease. I mean, at the core of it, the disease is very much the same across all people. But then when you begin to break it down into the effects of different risk factors, you begin to see significant differences.”

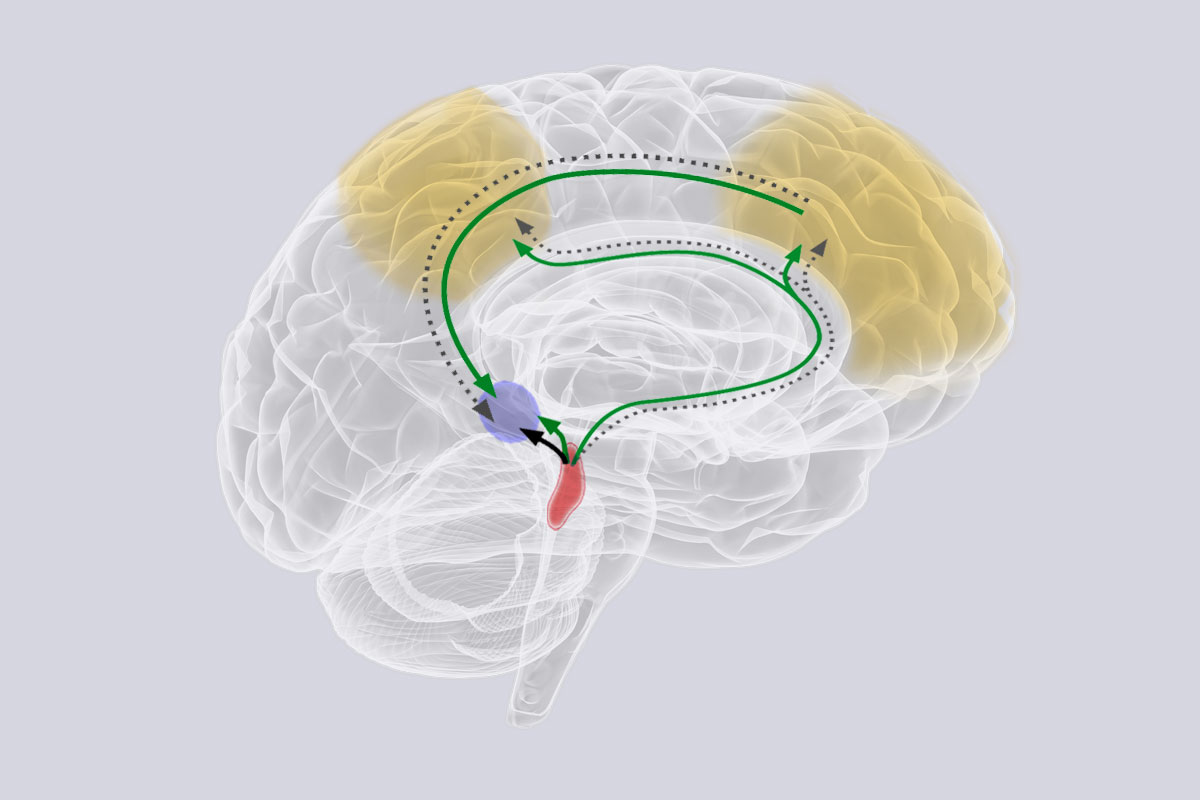

“And in recent years there’s been a greater emphasis on sex differences in the more we look, the more differences between the male brain and the female brain that we find.”

Learn more about Professor Pike and his work at https://gero.usc.edu/faculty/pike/

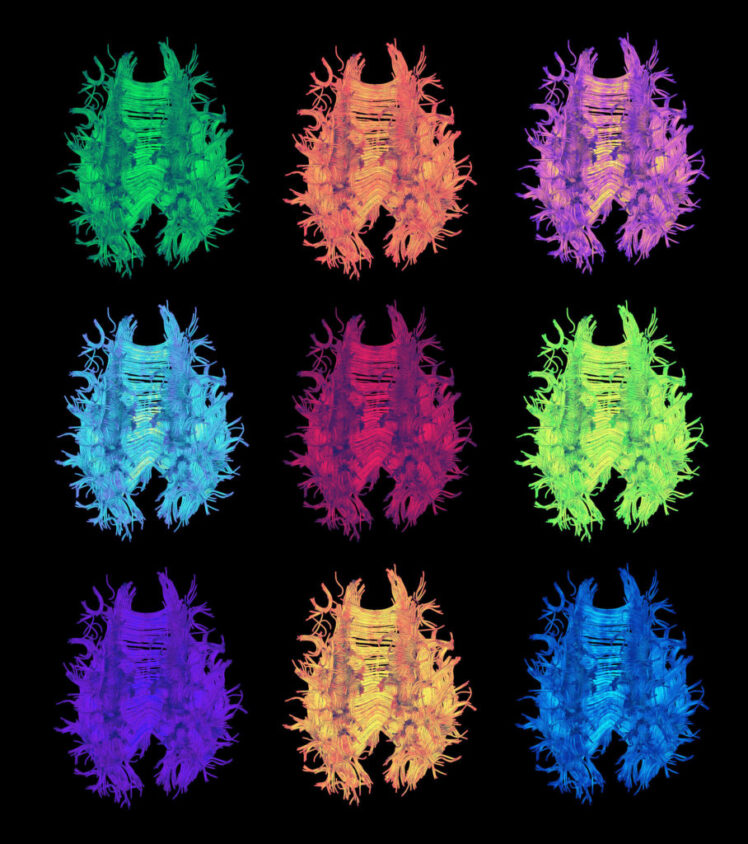

Brendan Miller is a neuroscience PhD student in the Cohen Lab. Miller, who recently earned a Young Investigator Award from Alzheimer’s Los Angeles (ALZLA), spoke to us about his research studying mitochondrial mutations in Alzheimer’s disease.

A: We know that mitochondrial dysfunction is one of the earliest hallmarks of Alzheimer’s, but it’s still unclear what is actually driving that dysfunction. I am hoping that we can find new mitochondrial gene mutations that are driving that dysfunction, and then we can take models that have that mutation and try to fix them.

A: It’s a two-step process. First, we are doing big data studies to identify mutations, and then we bring it down to a molecular level — replicating those mutations in cells — to see what they’re actually doing, and trying to find the mechanism.

A: Most of the genetic studies that have been published have not looked at the mitochondrial DNA. There could be hundreds of really small mitochondrial genes that have been overlooked. We are looking at mutations in these small mitochondrial genes. It is exciting to see if we can look at this uncharted landscape, identify which small genes are important and eventually target treatments toward them.