Researchers have proposed a new approach for the future study of Alzheimer’s disease, one that takes into account both environment and genetics and provides a more comprehensive view of disease risk, including how risks have changed throughout our species’ history.

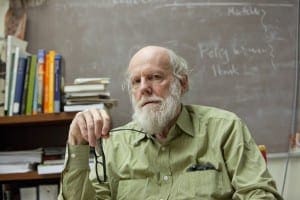

Caleb Finch, University Professor and ARCO/William F. Kieschnick Professor of the Neurobiology of Aging at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, and Alexander Kulminski of the Social Science Research Institute at Duke University have outlined a framework called the Alzheimer’s Disease Exposome. This framework addresses major gaps in understanding how environmental factors interact with genetic factors to increase or reduce risk for the disease. Their theoretical article appeared in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association in September 2019.

“We propose a new approach to comprehensively assess the multiple brain-body interactions that contribute to Alzheimer’s disease,” Finch said. “The importance of environmental factors in gene-environment interactions is suggested by wide individual differences in cognitive loss, particularly among people who carry genes that increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Endogenous and exogenous factors

The proposed AD exposome includes macrolevel external factors, such as living in rural versus urban areas, exposure to pollution and socioeconomic status, and individual external factors, such as diet, cigarette smoking, exercise and infections. This exogenous (external) domain overlaps and interacts with endogenous (internal) factors, including individual biomes, fat deposits, hormones and traumatic brain injury, which has been observed in professional boxers who develop Alzheimer’s. “Analysis of endogenous and exogenous environmental factors requires consideration of these interactions over time,” Finch said.

The researchers assume that some interactions can change factors of the exposome, describing, for example, a “lung-brain axis” for inhaled neurotoxicants of air pollution and cigarette smoke, and a “renal-cardiovascular disease-brain axis” for renal aging driven by diet and hypertension. Each of these axes may have different gene-environment interactions for each risk gene.

Finch has also studied the human exposome for clues on how humans have evolved and adapted to changing environmental factors that can influence Alzheimer’s risk, including air quality. Genes that helped humans survive exposure to ancient toxins, including pollen, woodsmoke and other airborne contaminants, may be the same genes that influence human resiliency to modern pollution from fossil fuels and cigarette smoke, according to a study coauthored by Finch and Benjamin Trumble of Arizona State University and published in the December 2019 issue of The Quarterly Review of Biology.

Millions of years before humans had to contend with engine exhaust, early hominids faced airborne toxins ranging from savanna dust and pollen to fecal particles from the large herds of prey animals they followed, Finch and Trumble wrote. Certain genes, including the gene for an immune cell protein called MARCO, may have evolved to better clear toxic smoke particles from lungs in humans. However, other proteins that help break down airborne toxins also leave behind fragments that damage tissues. In the face of more constant pollution exposure, having higher amounts of these damaging byproducts may now do more harm than good.

How environmental and genetic risk factors interact

Increasing age is the most important known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, but many other risk factors, including environmental exposures, are poorly understood. The authors note that previous studies of Swedish twins by USC’s Margaret Gatz suggested that half of the individual differences in Alzheimer’s disease risk may be environmental.

The two classes of Alzheimer’s disease genes are considered in the exposome model. One class, called familial Alzheimer’s genes, is made up of dominant genes, meaning that someone who inherits them will ultimately develop Alzheimer’s. The other class includes gene variants like apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4), where risk increases along with more copies of the genes. Among carriers of APOE4, a few people reach age 100 and older without ever developing the disease — demonstrating that environmental risk is contributing to that variability.

The researchers provide an “underappreciated” example of a study showing that the onset of dementia was a decade earlier for carriers of a dominant Alzheimer’s gene who lived in cities and who came from lower socioeconomic backgrounds or had less education. “Environmental factors, including exposure to air pollution and low socioeconomic status, shifted the onset curve by 10 years,” explained Finch. “It’s in the research literature, but until now no one has paid sufficient attention to it.”

Photo by John Skalicky

Other recent examples come from Finch’s research on the gene-environment interactions between parasitic infections and the Alzheimer’s risk gene APOE4. Among a preindustrial tribe of Bolivian people called the Tsimane, the presence of the gene along with chronic parasitic infections seemed to lead to better, not worse, cognition. Finch says the startling results provide an example of how the exposome concept could lead to enhanced understanding of risks for dementia.

The future of exposome-based research

Many studies are looking at conditions such as heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, obesity and diabetes with the goal of understanding how reducing risk factors for these conditions could reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Additional research — including studies for which Finch is the co-principal investigator — examines how urban air pollution contributes to accelerated brain aging and dementia risk.

The exposome concept was first proposed by cancer epidemiologist Christopher Paul Wild in 2005 to draw attention to the need for more data on lifetime exposure to environmental carcinogens. The exposome is now a mainstream model, eclipsing previous characterizations of environmental factors as affecting risk one by one.

“Epidemiologists have been using the exposome to have a broader outlook for whatever they’re studying, whether it’s lead toxicity or head trauma,” Finch said. “It’s our point that a number of things need to be considered for interaction, and many effects are additive.”

Additional reporting by Beth Newcomb; illustration by Natalie Avunjian