Around the world, heart disease is the leading cause of death. In the US, this has been the case since the 1930’s when it gradually replaced infections, like pneumonia and tuberculosis. As lifespans have extended over the last century, heart disease has been considered a modern affliction brought on by lifestyle factors like cigarette smoking, unhealthy diets and too little exercise.

But evidence has emerged that this is not necessarily the case.

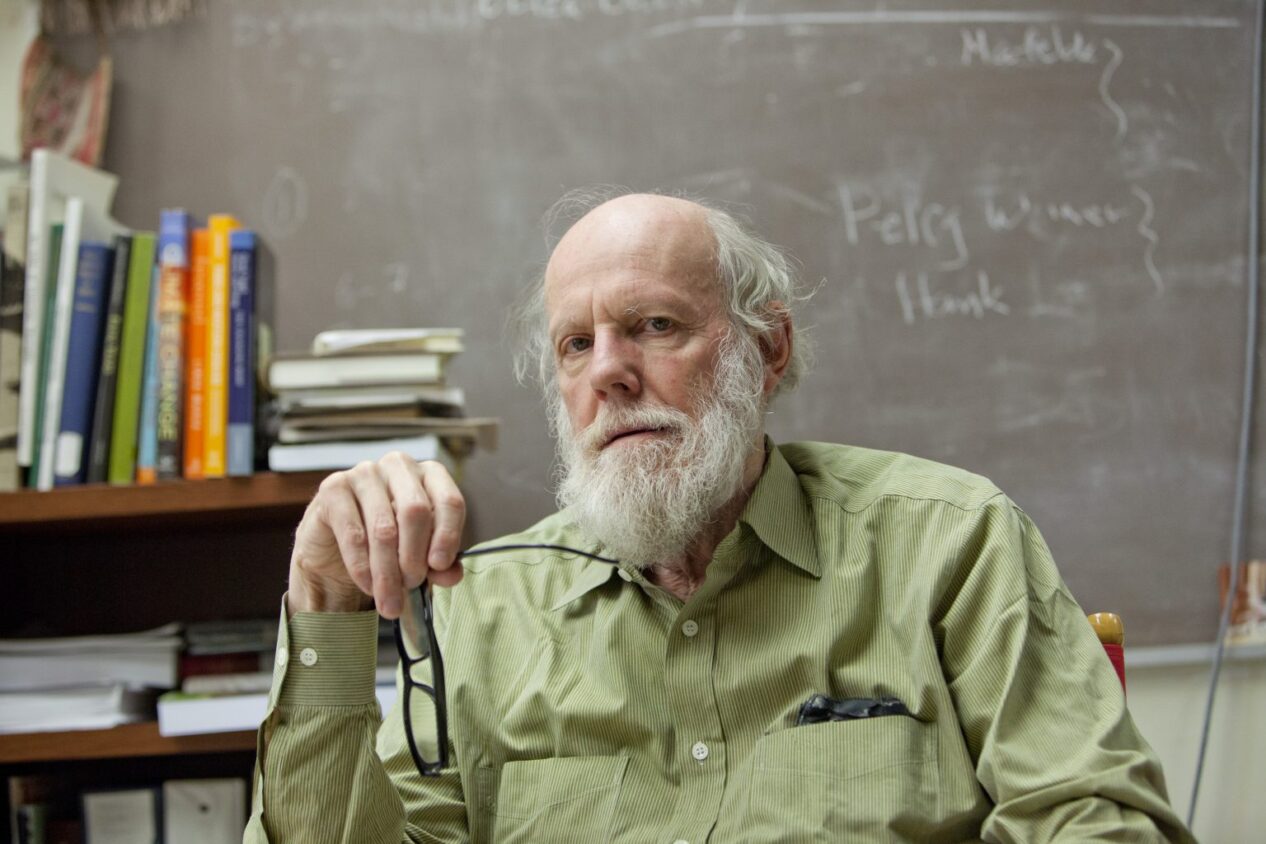

In a recent episode of the USC Leonard Davis School podcast Lessons in Lifespan Health, biologist Caleb Finch discusses research he has been a part of that suggests that a hardening of the arteries may be part of the general process of aging, regardless of time and place.

First, Finch joined a team of researchers who studied mummies from four different regions around the world—sometimes sitting with them in hospital emergency rooms, waiting for a turn to see inside their remains using CT machines meant for patients. The resulting scans show evidence, in their ancient arteries, of calcium deposits—an early sign of heart disease

“The oldest individual may be the Tyrolean iceman, Ötzi as he’s called, who is… 3000 BC, living in the Copper Age and both of his carotid arteries were calcified,” Finch said. “He died because of a wound from a weapon. But, I think it’s a conclusion that’s fairly robust that there are, at least in the last 10,000 years in the Neolithic area era, people [that] have had some level of atherosclerosis. Although, it may not have been a major cause of death or disability.”

To explore this further, Finch enlisted his cardiology colleagues from the mummy team to join an ongoing global collaboration, led by anthropologists Hillard Kaplan and Mike Gurvin, to study the heart health of the Tsimane, a pre-industrial tribe living along the amazon river in Bolivia. It turns out that when the Tsimane live to an old age, they show very low levels of heart disease.

“It’s surprising because, in all the industrial populations in the world, heart disease is the dominant cause of death,” said Finch. “So, here’s the population which has 95 percent less heart disease as a cause of death. That’s very interesting.”

When it comes to arterial age, an 80-year-old Tsimane looks like an American man or woman in their mid-50s.

“So, what has turned out to my cardiologist’s surprise, when they actually started imaging the older Tsimane that they have almost no vascular disease, and stroke and heart attack are very rare causes of death. … Death is [mostly] caused by infections, or associated with infections,” said Finch. “And it’s a wonderful mystery as to how the rate of blood vessel aging is so much slower in this population than in North America and Western Europe. So we’re studying this in terms of diet, in terms of stress, in terms of disease load, and, of course, we are looking at their individual genetics.”

The Tsimane’s heart health is also surprising because they having high levels of inflammation—a marker in our modern world that has been associated with an increased chance of having a heart attack or stroke.

“And, that’s why the Tsimane project is so fascinating because they have lifelong high inflammation, and we all would have predicted and did that they would have had faster aging for these same diseases. But it’s not the case, at least for that heart disease,” said Finch.

Finch suspects that there is a difference in the source and impact of the Tsimane’s inflammation and what we experience in our industrial society, where inflammation is driven by our diets, air pollution, tobacco smoke and our own fat deposits. For the Tsimane, inflammation is likely a response to infections, Finch said.

“I joined this project really 15 years ago. And Eileen Crimmins also was with me on this, to study how inflammation is manifested in this unhealthy environment where almost everybody has chronic parasites and frequent lung and G.I. disease,’ said Finch. “Well, if you’re carrying a high load of infections, you’re using a lot of your nutrient intake to combat the infections and to repair tissue damage. So, the Tsimane have very low levels of blood lipids at the levels that are reached by the modern statins and other drugs that control blood lipids in our high fat intake world. So, my hypothesis is that they simply are using this energy elsewhere, and that is part of why there is so little accumulation of a blood vessel fat with aging.”

Finch said the lesson for Western societies is to maintain low blood lipids and low blood sugar.

“Of course nobody wants to consider—or should—getting your belly full of parasites to do that. In our relatively healthy, somewhat sterile, environment can do it with choice of diet and exercise and, as needed, the drugs are now available to control both blood lipids and blood sugar,” he said.

Finch and his colleagues are now interested in understanding brain aging in the Tsimane. Along with USC colleagues Andrei Irimia and Margy Gatz, he has begun research involving cognitive testing and brain imaging. They are looking at whether the Tsimane also have lower rates of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia than we do.

“We predict what’s good for the heart is good for the brain, that, if their heart function is as good as we think it is, they should have better brain function at later ages then in North America and Europe,” he said.

Finch hopes these findings will help inform our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease. He expects results within the next five years. He also realizes it is one of the last opportunities to learn about the effects of the Tsimane way of life, where they grow or hunt their food, are physically active and don’t smoke much.

“Some of the young already have cell phones, some of them are doing day work for the timber companies and going to San Borja and spending their money on McDonald’s,” he said. “So, the next generation within 10 years, there’ll be remnants of the older lifestyle, and so we’re catching them at the last possible moment before they leave this traditional lifestyle, and that is gone.”

Closer to home, Finch is leading a large research project looking at the role of air pollution in Alzheimer’s disease. He continues to look at how genes and environments interact to impact aging. His studies of mummies and the Tsimane show us there is much to be learned from unexpected findings.

“So, that’s one of the great pleasures in science,” he said. “As you put your best thoughts together and let them be challenged, looking at different varieties of lifestyle, and it turns up that there are things that seem paradoxical that give deeper insights into basic mechanisms of aging.”

Listen to this episode and other podcasts at Lessons in Lifespan Health.