Editor’s note: The below column was first published in American Society on Aging’s Generations in January 2021.

The United States has experienced significant milestones in equity for sexual and gender minority (SGM) individuals, from the 1973 removal of homosexuality as a mental illness in the DSM to the 2015 legalization of same-sex marriage. While these events mark notable progress for SGM individuals, considerably more work needs to be done to close disparities in this population.

Rarely addressed are the disadvantages and cumulative risks faced by older adults within the SGM population, because few studies on aging in older adults focus on sexual orientation and/or gender identity. This is of utmost concern as older SGM adults are a rapidly growing population, and like the larger SGM population, they are racially and ethnically diverse.

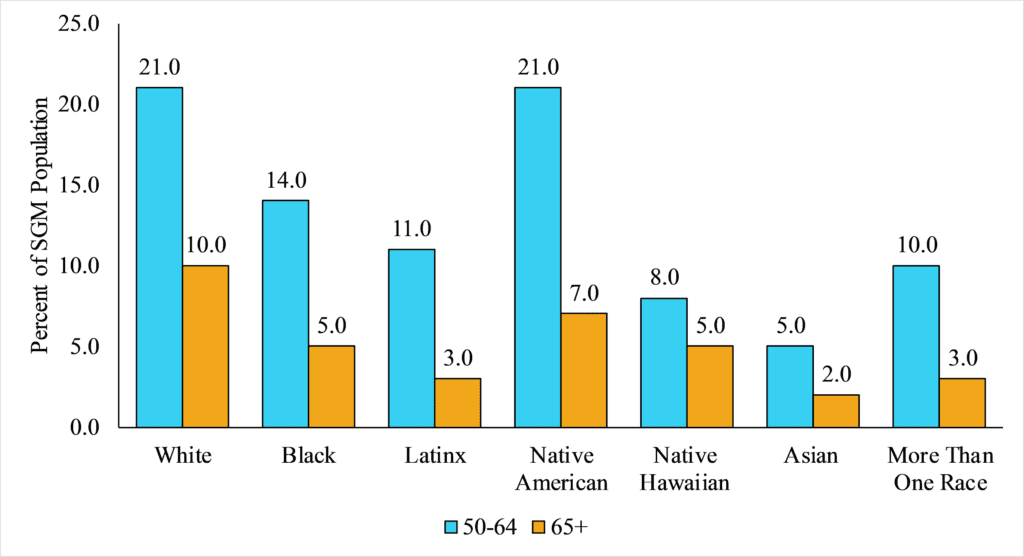

Approximately two in five SGM older adults are persons of color, with Native Americans making up the largest proportion of SGM older adults of color (28 percent), followed by Black (19 percent) and Latinx (14 percent) older adults (see Figure 1, below). Although the experiences of SGM older adults of color are not well-documented, evidence shows that SGM older adults and older adults of color are disproportionately affected by poverty and mental and physical health conditions due to differences in life opportunities that took shape earlier in the life course.

Figure 1. Racial/Ethnic Distribution of SGM Adults Ages 50 and Older in the United States. Source: Data are from the LGBT Demographic Data Interactive (2019) provided by The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Note: Universe is SGM Population.

However, the multiple marginalized axes of SGM identity and racial/ethnic identity compound disadvantages in these populations. These disadvantages are a result of structural discrimination and historically inadequate access to employment, education and other opportunities that limit the ability to build economic security and optimize health across the life course, and contribute to significant disparities in later life.

This article highlights how SGM older adults of color are increasingly vulnerable to isolation and poor mental health as they age, while simultaneously being excluded from the aging and health services they most need, due to their adverse interactions with social and economic power structures. Addressing the needs of the SGM population is paramount, and requires consistent and sustained efforts in advocacy, research and service for SGM older adults of color.

Social Isolation and Mental Health

Older SGM adults are more likely to live alone than are their heteronormative peers, and are less likely to receive assistance from partners and biological children as they age. Living alone is a strong risk factor for social isolation and is consequential for mental health. The effects of social isolation on mental health may be especially pronounced among SGM older adults of color as they came of age during an era where same-sex relationships were criminalized and severely stigmatized, nonbinary gender identities were invisible and segregation and overt discrimination were lawfully enforced.

Evidence shows that SGM older adults have an elevated risk of depression, distress, suicide, addiction and substance misuse, which may be linked to a lifetime spent on the receiving end of discrimination.

‘DUE TO HISTORICAL AND STRUCTURAL RACISM, OLDER SGM ADULTS OF COLOR ARE MORE LIKELY TO DELAY CARE.’

However, SGM older adults’ proficiencies in forming identity, community and support networks may confer positive resources that help reduce the risk of isolation, distress and mental health risks as they age. Of note, studies have found inconsistent evidence of elevated psychological problems or distress among SGM older adults of color, acknowledging the resourcefulness, resilience, agency and effort these older adults have used and are using to survive into older adulthood. Given the influence of race/ethnicity and SGM identity on mental health and well-being, future research and programs must begin to disentangle important racial/ethnic subgroup differences among SGM older adults.

Access to Support and Services

Access to organizations and centers that provide support and services for older SGM individuals is limited. Many are staffed by volunteers and lack the funding needed to provide aging-specific and SGM-specific services and support. During the pandemic, organizations are projecting a substantial decline in revenue across multiple sectors (e.g., fundraising, programming and corporate giving) and are reducing budgets for needed services and supports. Older SGM adults face many uncertainties regarding their health and well-being, worries that are exacerbated amid the isolation due to social distancing policies.

Moreover, due to historical and structural racism, older SGM adults of color are more likely to delay care, given the fear of discriminatory practice and lack of culturally competent service. Thus, it is imperative to understand how the greater vulnerabilities associated with being an older SGM adult of color increases their need for support and services. However, older SGM adults of color are the least likely group to have access to these supports and services due to the lack of societal and capital investment in their health and well-being.

It’s Past Time to Address Inequities

While, in general, societal acceptance of sexual and gender identity is widening, SGM supports and services remain inequitable, placing older SGM adults of color at an even greater risk for significant health disparities as they age. Given the increasing diversity of our aging society, it is imperative that we begin to address the aging and health needs of older SGM adults of color. This requires recognizing the historical legacies of structural discrimination and present-day practices of marginalization that exclude older SGM adults of color from seeking or accessing inclusive, culturally competent patient-centered care.

Additionally, seeking input from marginalized segments of this population and recognizing the diversity of this community also can reveal unique sources of coping and resilience among SGM older adults of color, who have survived and often thrived well into older adulthood, despite the adversity they face.

As researchers in aging, we recognize the need for nationally representative data among older adults that measures gender and sexuality as a spectrum in diverse populations, to fuel new knowledge and opportunities for progress for SGM older adults of color.

Mekiayla Singleton, MSW, is a doctoral student in the Leonard Davis School of Gerontology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. She can be contacted at mekiayls@usc.edu. Catherine García, PhD ’20, is an assistant professor of Sociology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in Lincoln, Neb. She can be contacted at catherinegarcia@unl.edu. Twitter: @latinageron. Lauren Brown, PhD ’18, MPH, is an assistant professor of Public Health at San Diego State University. She can be contacted at lbrown2@sdsu.edu. Twitter: @profbrownnnn.

Headline quote is from James Baldwin.