Postdoctoral Fellow Uchechi Mitchell

Older Americans who did not graduate from high school feel they have less control and hope in their lives than those who completed a high school degree or better, according to a national study led by USC researchers.

“Higher levels of educational attainment offer some protection against declines in sense of control and hope as people age,” said Uchechi Mitchell, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral fellow at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology and the USC/UCLA Center for Biodemography and Population Health.The findings, based on responses to the national Health and Retirement Study, contribute to scientific evidence that education affects our well-being and health in later years.

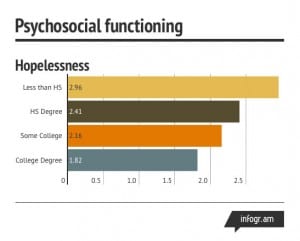

Hopelessness was greatest among the least educated, and their hopelessness worsened over time, the researchers found. The increase in hopelessness was also associated with health problems and disability.

Mitchell also offered a cautionary note on interpreting the study’s results.

“This does not mean that someone with a college degree may not experience these declines or that someone with a high school degree is destined to feel in less control of their lives or hopeless,” said Mitchell, who is also affiliated with the Minority Aging Health Economics Research Center of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics.

The study was published online on March 24 in the Journals of Gerontology: Social Science.

Psychosocial functioning

The researchers studied changes in 8,945 participants’ responses to a self-administered questionnaire of the Health and Retirement Study. The longitudinal study was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration to track changes in Americans 50 and older as they leave the work force.

Participants, aged 52 and older, answered the survey twice in four years. Half of the respondents completed it in 2006 and again in 2010. The other half completed it in 2008 and again in 2012.

The average age of respondents was 65. They all reported which level of schooling they had completed: less than high school, high school, some college, or a college degree or higher.

The survey questions measured three aspects of psychosocial functioning: mastery (personal efficacy), perceived constraints (obstacles that may hinder goal achievement) and hopelessness. The responses to statements such as “I can do just about anything I really set my mind to” ranged from 1 — strongly agree — to 6 — strongly disagree. The researchers then averaged the values from the statements.

(On that statement, 88 percent of those who didn’t have a high school degree agreed with it, compared with 90 percent with a high school degree, 92 percent with some college and 93 percent of those who completed college or more.)

This scale was used in prior studies to measure a general sense of hope and control over one’s life.

Support networks

Participants answered questions about their support networks, including whether a spouse had died or they had lost support from a spouse or partner through divorce or separation. They answered questions about how much they felt their family or friends understood their feelings, whether they could be relied upon for serious problems and whether they could confide in them.

Respondents also reported any health conditions and difficulties or limitations performing daily activities such as dressing, eating and walking.

One in every eight respondents reported having at least one physical limitation, nearly 45 percent had a health condition and 20 percent were depressed.

Hopelessness increased for respondents who at some point within the four years of the surveys had suffered a disability or who reported a loss of social support from family or friends.

“We did not observe an association between spousal loss and any of our measures of psychosocial functioning,” the researchers wrote. “There was an association, however, between loss due to divorce/separation and perceived constraints and hopelessness.”

Twice in four years, participants responded to questions about how they felt in their old age. Researchers rated the answers on a scale of 1 to 6, with 6 representing the worst, and then calculated the averages and mean responses according to their level of schooling. (USC Graphic)

Economic status and financial well-being often are associated with a high level of educational attainment, but Mitchell emphasized that this study did not examine their influence. Instead, she said, the study focused on education and the psychological and social aspects of aging.

“Although greater educational attainment can potentially lead to increased earnings and greater financial stability, this is not always the case; the relationship depends on other factors such as a person’s occupation and marital status,” Mitchell said. “At older ages, education may be more important for psychosocial functioning than individual earnings or household income because many older adults are retired. Education is a more stable resource that often doesn’t change in old age.”

The study co-authors were Assistant Professor Jennifer Ailshire, doctoral candidate Lauren Brown and AARP Professor of Gerontology Eileen Crimmins — all of USC Leonard Davis; and Morgan Levine, postdoctoral fellow at UCLA.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (T32-AG000037, R00-AG039528, P30-AG043073 and R24-AG045061).

USC and aging research

Aging and the various diseases and conditions associated with it are among the intractable problems that USC researchers in multiple disciplines are seeking to unravel. Efforts to understand the causes of aging and to find preventive interventions and precise treatments are much more pressing as the baby boomer generation ages. The U.S. Census Bureau predicts that Americans aged 65 and older will represent one-fifth of the U.S. population in 2020, up from roughly one-seventh today.

–Emily Gersema