New research from USC has uncovered a previously unknown genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. The study provides insights on how these conditions, and other diseases of aging, might one day be treated and prevented.

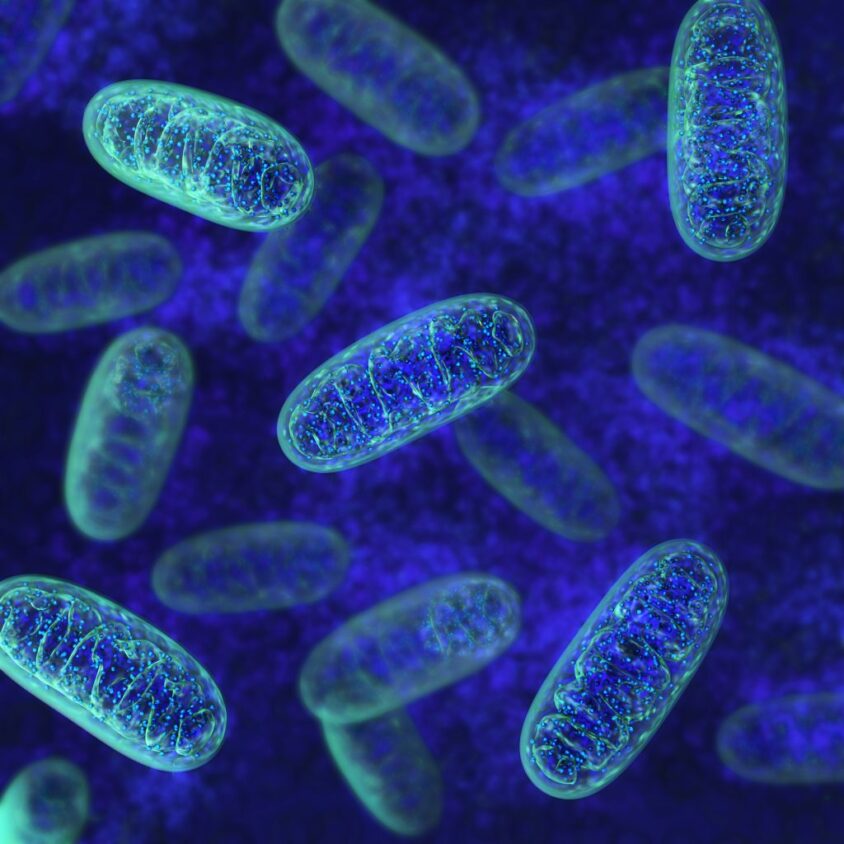

The research from the Cohen Lab at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology sheds new light on the protective role of a naturally occurring mitochondrial peptide, known as humanin. Amounts of the peptide decrease with age, leading researchers to believe that humanin levels play an important function in the aging process and the onset of diseases linked to older age.

Senior author, Dean Pinchas Cohen

“Because of the beneficial effects of humanin, a decrease in circulating levels could lead to an increase in several different diseases of aging, particularly in dementia,” said senior author Pinchas Cohen, dean of the USC Leonard Davis School and one of three researchers to independently discover the existence of humanin 15 years ago.

The study, Humanin Prevents Age-Related Cognitive Decline in Mice and is Associated with Improved Cognitive Age in Humans, led by Kelvin Yen of the USC Leonard Davis School, appears online on Sept. 21 in the Nature-published journal Scientific Reports. Among the findings, the researchers discovered a significant difference between the circulating levels of humanin in African-Americans, who are more impacted by Alzheimer’s disease and other diseases of aging, as compared to Caucasians.

“We have now discovered a novel underlying biological factor that may be contributing to this health disparity,” said Yen, a research assistant professor of gerontology.

Because humanin is encoded within the mitochondrial genome, the research team examined the mitochondrial DNA for common genetic variations known as SNPs (pronounced snips) that could explain the differences between humanin levels. According to the paper, after sequencing the entire mitochondrial genome of all samples to determine if any SNPs correlated with humanin levels, they identified a genetic variation that was associated with a 14 percent decrease in circulating humanin levels.

This provides the first evidence that a variation in the sequence of a mitochondrial peptide is associated with a change in the level of peptides and the first conclusive demonstration that mitochondrial peptides are encoded in and regulated through mitochondrial DNA, Cohen said.

Lead author Kelvin Yen

The team subsequently examined the effect of this SNP in a separate large cohort of participants from the Health and Retirement Study, a longitudinal study of approximately 20,000 individuals over the age of 50 in the United States, of which more than 12,500 individuals consented to DNA analysis. Using this data set, the researchers report finding that the unfavorable version of this SNP, associated with low levels of the humanin peptide, is also associated with accelerated cognitive aging, providing the first demonstration linking a humanin SNP in the mitochondria to cognitive decline in people.

The paper also shows that in mice, injections of humanin delay cognitive decline associated with aging, proposing a possible therapeutic role for humanin-related drugs. The mechanism through which humanin acts to mediate these effects involves suppression of inflammation systemically, as well as specifically in the brain.

Cohen’s research team included multiple collaborators from USC, Yale University and the National Institutes of Health.

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences), the American Federation for Aging Research, and the Department of Defense.

Senior author Cohen is a consultant and stockholder of CohBar Inc., which is based in Menlo Park, Calif., and conducts research and development of mitochondria-based therapeutics.