When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, administrators at Contra Costa Health Plan noticed a distressing trend: their Latino patients seemed to be getting sicker than patients of other ethnicities. So the public health plan for the Northern California county asked USC researchers to analyze their raw data to see what they would find.

What Mireille Jacobson learned when she started crunching the numbers on Covid outcome disparities surprised both her and the health officials: Latinos were more likely to test positive, more likely to be hospitalized and more likely to die of Covid than white, Black or Asian patients in the same health system. “We didn’t understand the magnitude of the differences between Latinos and other groups,” said Jacobson, associate professor of gerontology at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology. “Putting a number to it was kind of alarming.”

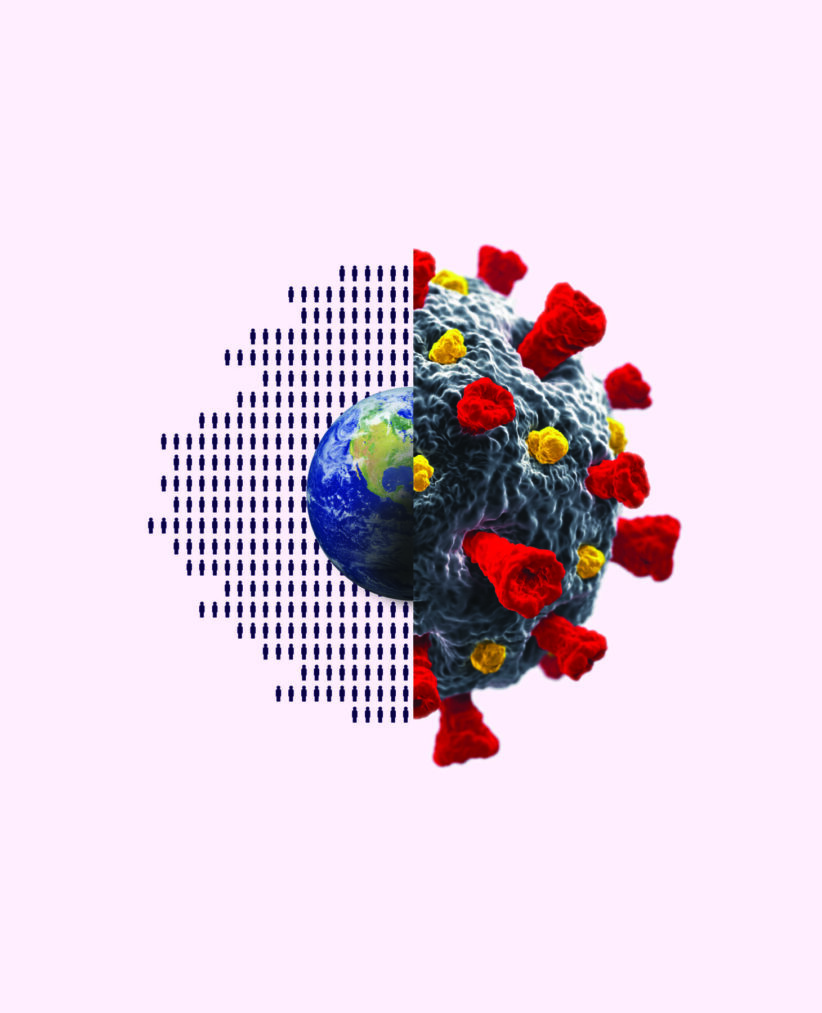

For years, USC Leonard Davis researchers have studied U.S. health and health disparities. They’ve charted with dismay how American life expectancy has slid further and further behind that of residents of other wealthy nations. Recently, they’ve been finding that the Covid pandemic, and Americans’ response to it, has introduced new complications and made that gap wider still.

“We’ve gotten progressively worse than other high-income nations over a substantial period of time, probably since 1980,” said Eileen Crimmins, the AARP Chair in Gerontology at the Davis School of Gerontology. “And now, with the pandemic, it’s just getting much worse.”

The main reason, pre-pandemic, Crimmins said, was a decrease in the rate of improvement in death from cardiovascular disease. In an article published last year in Nature Aging, Crimmins and colleagues found that increased life expectancy among a majority of wealthy countries was lower between 2011 and 2017 than in the six previous years, in large part due to decreases in the rate of decline in cardiovascular disease. But in the United States (as well as in Iceland) there was actually a decrease in life expectancy during that period.

The reasons for that, Crimmins said, are structural and political: lack of a strong social network; a health care system that works for those who can get into it, but which leaves others struggling to access even basic medical care; the easy availability of guns, which leads to more firearm deaths; and the opioid epidemic, which has resulted in “deaths of despair.” Obesity plays an additional role in decreasing cardiovascular health, Crimmins wrote in the paper.

“Many people think we have good health and long life expectancy in the United States,” she said in a recent interview. “But we are not nearly as good as our peers.”

Thanks to Covid-19, U.S. life expectancy has decreased even further. In 2020 alone, the virus decreased American life expectancy by 1.31 years—from 78.74 years to 77.43 years— wrote Theresa Andrasfay, a postdoctoral scholar at the Leonard Davis School, in an article published in JAMA Network Open in June 2021. In a subsequent study published in PLOS ONE in August 2022, Andrasfay and her co-author, Noreen Goldman of Princeton University, found that the decrease in life expectancy appears to have continued through 2021, despite the availability of Covid-19 vaccines.

But Andrasfay and Goldman found significantly worse outcomes for Blacks and Latinos. They reported that while life expectancy for whites dropped by .94 years in 2020 due to the Covid-19 virus, for Latinos it dropped by 3.03 years and for Blacks by 1.9 years.

“We think it’s a combination of a lot of social factors,” Andrasfay said, noting that one particular challenge those populations faced was working in essential jobs that increased their exposure to the virus. Also, many people in those populations came into the pandemic with ailments like diabetes and risk factors such as obesity that made them more susceptible to serious illness, she said.

“We still don’t fully understand why the Black and Latino populations were infected more,” Andrasfay said. “It seems to be a confluence of many factors that puts them at higher risk.”

Pre-pandemic, the life expectancy gap between Blacks and whites had been narrowing. “But then Covid erased those gains,” she said.

The pandemic also nearly erased the “Latino paradox,” so called because Latinos in the U.S. have historically had similar or better health outcomes than whites, even though they have lower average income and education levels. But diabetes and other chronic health conditions had been on the rise in this population, Andrasfay said. Usually, such issues would take decades to impact mortality risks, but Covid accelerated that process, she said.

And then there was the fact that many Latinos worked at the kind of low-income jobs that couldn’t be done from the safety of their homes. That “suddenly became a risk factor for mortality in a way that hadn’t really existed in the past,” Andrasfay said.

Like Andrasfay, Jacobson found the Latino population to be particularly at risk. Her study of racial and ethnic differences in Covid-19 testing and outcomes included data on more than 84,000 adults at Contra Costa Regional Medical Center who were enrolled in that county’s Medicaid managed care plan.

Jacobson and her colleagues, however, controlled for various risks, like pre-existing health conditions, demographics and neighborhood factors. The Latino patients still fared worse than the other groups, even though they were disproportionately younger. “This tells us that going forward, for future pandemics, this is going to be a particularly vulnerable group,” Jacobson said of the research, which appears in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

After vaccines became available, Contra Costa officials asked the USC researchers to study strategies for getting reluctant patients to take the jab. The result, “Can financial incentives and other nudges increase COVID-19 vaccinations among the vaccine hesitant? A randomized trial,” was released last fall as a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper and was published this year in the journal Vaccine.

Jacobson first tried a tack that had often proved successful in the past with the flu vaccine: offering people modest sums of money in exchange for vaccination.

It didn’t work. “I don’t think we appreciated how strong the reluctance was,” she said. The monetary “nudge” strategy, however, worked for researchers in Sweden with the same vaccine, she said.

“But here, there were very strong beliefs about not taking this vaccine, for a variety of reasons,” she said. “One was a political belief, [and] another was a kind of safety fear because of how quickly the vaccines were developed.”

In fact, she said, Trump voters in particular became even less likely to get a vaccine when offered a financial incentive to do so. She speculated that people wondered, “Why do they have to pay me to do this? I knew something was wrong with this.”

As part of the same work, they also tried different types of public health messaging and created an easy online process to schedule vaccinations. The health system did even more, throwing “vaccination fairs” and rolling out a free ice cream cart. Nothing seemed to meaningfully change the behavior of the vaccine hesitant.

“It was really, really sad,” Jacobson said.

In the end, there was only one tool the health system didn’t try, but that’s because it’s one best enacted by governments or employers: mandates. Jacobson has come to believe that mandates are the only way to ensure community-wide inoculation. “We need stronger approaches if we think [getting vaccinated] is for the greater good,” she said. “We need things like ‘You can’t come into this store if you’re not vaccinated’ or ‘You can’t work at this job unless you’re vaccinated.’”

Andrasfay, Crimmins and colleagues looked at how personal behaviors might reduce the spread of the virus. In a paper published in the January 2022 issue of the American Journal of Public Health, they reported that people who practiced certain social distancing measures could significantly reduce their likelihood of getting Covid, even when transmission rates were high. For instance, they found that people who reported attending gatherings of more than 10 people were 40% more likely to get Covid than those who didn’t. Even attending small gatherings increased the risk of Covid diagnosis by 30%, the researchers found.

“The takeaway here is that even if you’re in an area where there are high Covid cases, if you choose to limit your social interactions, it helps reduce your risk” of contracting the virus, Andrasfay said.

Even if you have gotten Covid once and it was mild, you should try to avoid getting it again, Crimmins said. In 2010, Crimmins and colleagues studied the health of people who were in utero during the 1918 flu pandemic. Those whose mothers were exposed to the virus when they were in utero were more likely to have heart disease when they were elderly than those who were not exposed to the virus in utero.

Jacobson said that the Covid pandemic, as well, may “have long-term effects on people that will be subtle all their lives, but [that] can have a substantial effect in terms of the population having worse health over time,” she said.

It’s ironic and more than a little frustrating, she said, for researchers to see anyone taking such a threat casually. “For decades, we’ve spent a lot of time and money trying to save lives by doing extraordinary things, and spending extraordinary money to keep people alive,” and such innovations receive a lot of attention, she said. “But the adoption of robust, evidence-based public health policy, as well as more people engaging in simple preventive behaviors, might have a bigger impact on population health than anything else right now.”